S. Sixtus and the Arabic epitaph

The next venture, following those celebrated in the inscriptions on the Cathedral front, was the expedition in 1087 to al-Mahddya, today part of Tunisia. The Pisan and Genoese fleets triumphed on 6th August, the feast day of St. Sixtus (S. Sisto). From then on this saint became the patron saint of Pisa’s victories.

The Church itself is a monument recording the enterprise and the objects in it are a way of telling people about the closeness and complexity of the relationship between Pisa and the Islamic world in the Middle Ages.

Looking at the simple Church front, we see it is decorated at the top with a row of pottery bowls: this type of ornamentation is also found in other medieval churches of the period but especially in cities like Pisa, with strong commercial ties around the Mediterranean.

In fact many of Pisa’s Romanesque churches are richly decorated with pottery bowls, cemented high up on the outside walls, under the eaves, and on the church fronts, rather like jewels circling the top of a crown. They were there in fact to reflect the sunlight from the shiny, jewel-like inner surface of the basins. And for this reason the bowls from the Islam world were chosen. They were highly prized because of their elegance and their mirror-like enameled finish. The original bowls are now in the San Matteo Museum. Those we see on the Church front are replicas. Nonetheless, they still tell of the relations between Pisa and north-Africa in the 11th century, in quite a different way and voice from those of the carved inscriptions on the Cathedral front. There was not merely hatred, war, revenge and robbery between these two worlds: in the 11th century al-Mahdīa was under the dominion of the Zirids, a Berber dynasty connected to the Egyptian Fatamid caliphate. With Zawila on its outskirts it was one of the key trading places in the Mediterranean. Its walls surrounded warehouses and depots for merchandise. Christian merchants came from many parts, certainly from Amalfi and Pisa. Moreover, we know from a letter of 1063 that Pisan danari were commonly used in exchanges. It was through these – we must presume mainly peaceful – exchanges, that huge amounts of merchandise from north Africa reached Pisa. And among the goods were the pottery basins that decorate the Church of San Sisto and other churches in the city, used also to adorn the tables of the wealthier households.

However, al-Mahdīa was also a headquarters for piracy. The persisting danger from Saracen raids together with a series of political circumstances at home, prompted Pisa, Genoa and Amalfi to fit out a fleet in 1087. The aim was to rescue the Christians imprisoned in the Zirid dominions and reduce their king Tamim ibn al-Mu‛izz to submission. According to a poem, the Carmen in victoriam Pisanorum, written at the time this person “with his Saracens … devastated Gaul, took all the people of Spain prisoner and troubled all the Italian coasts, with raids as far afield as the Eastern Empire and Alexandria. There is no place in the whole world nor island in the sea that the horrendous wickedness of Timino does not trouble: Rhodes, Cyprus, Crete and Sardinia, and with them, noble Sicily.”

The punitive expedition took place in the summer of 1087 but since there were 300 or 400 ships in the fleet, it must have taken several years to prepare. Its aim was both political and economic; the victorious Christians demanded not only that the Zirid sovereign release the prisoners, but forced him to pledge he would cease piracy and pay tributes to Rome. Moreover, Pisans and Genoese were to be exempt from customs duties and he was to pay a huge sum in compensation. Part of the plunder was used to build this Church, dedicated to San Sisto because the victory fell on this saint’s day, and part of contributed to continuing the construction of the Cathedral. This enterprise made a great impression on people of the time because it gave both Christians and Muslims the idea that when united, Pisa and Genoa were invincible on the seas and were therefore the winning team for any and all ventures undertaken in the Mediterranean.

However, the Church and the expedition against al-Mahdīa also tell another story: although Pisa had the power to organise and finance far-reaching military ventures, in 1087 it did not yet have a Comune or Consuls. Perhaps for this reason San Sisto was more than just a monument to a great military victory: it became the city’s church par excellence. A site where to build it was chosen, in the heart of the city, probably close to the marquis’ ancient seat of power. From its earliest days, the Church was used for important city meetings; solemn public deeds were drawn up there and it was placed under the patronage of the governors of the Commune: in other words, from the outset it was a civic church. The entire city recognized it as a symbol of the exercise of communal power.

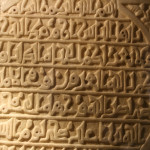

Probably because of its strong connections with the glories of the city and Commune, it was decided to place an important article of plunder – an inscription in Arabic stolen from the Balearic Islands in 1115 – here:

In the name of God, the Merciful, the Merciful! Men: that which God promises is true! Do not let worldly things mislead you ! May the Deceiver not deceive you concerning God! The Emir Abū Nasr is dead – may God let his face shine on Muhammad …

These are the opening lines of the remarkable funerary inscription, unfortunately now incomplete, carved in Cufic script. Thanks to its transcription and José Barral’s studies, we know that it was carved in honour of the Emir al Murtadà, who died on Saturday 7th January 1094. Since the Pisan venture at the Balearic Islands took place between 1113 and 1115, the Emir was definitely not killed by Pisans. The stone was stolen as plunder from the war after Pisa’s victory and was displayed to public view – as was the custom of the time – above, beside or inside a sacred building.

Another magnificent example of this tradition is the griffin, a metalwork sculpture, that until 1828 stood on a pillar placed at the end of the roof ridge of the Cathedral apse. Today it is on show in the Cathedral Museum, and is replaced by a faithful copy. It dates from between the 10th and the 12th centuries and is one of the most beautiful Islamic works in bronze. Its flanks and breast are finely engraved with sacred invocations and decorations. Although we do not know when or on what occasion the griffin passed into Pisan hands, we do know that it is of mid 11th century Hispano-Arabian manufacture and many scholars accept that, like the engraving in San Sisto, it is part of spoils from the battle of the Balearic Isles.

The story of the Emir al Murtada and his elegant inscription is connected to another recently re-discovered story, it too carved into a marble plaque on the Cathedral front: the story of the unfortunate queen of Mallorca.

† Regia me prol[es g]enuit, Pise rapuer[unt]:

His ego cum nato bellica pr[eda] fui.

Maiorice regnum tenui. Nunc condita s[ax]o

Quod cernis iaceo, fine potita meo.

Quiquis es, ergo, tue memor esto conditionis

Atque pia pro me mente precare Deum

I was born of royal stock, Pisa captured me:

I with my son was the plunder of war.

Mine was the kingdom of Mallorca, now I lie enclosed

In the stone you see here, having come to my end.

Whoever you may be, then, remember your condition

And pray to God for me with devotion in your heart.

We see from this engraving that a queen of Mallorca was taken prisoner and brought to Pisa, probably at the same time as the engraving in Arabic and, probably, the griffin, together with – who knows how many – other riches. Living among Christians converted her, to the extent that on her death she was actually buried in the Cathedral. Thanks to Giuseppe Scalia’s research, we now know that this queen was probably a niece of Murtada (the Emir of the Arabic incision) and wife of Abu Rabi, another Balearic king, also known as king Burrabe, the last independent sovereign of this archipelago.

It must have been a source of great satisfaction to Pisa to have as a guest (or prisoner) such an important person and to have converted her. It was something to display with pride in the view of the most important people in the universe at the time: the Pope and the Emperor.

We do not know exactly the true status of this woman. Was she a guest or was she a hostage? Was she honoured or humiliated? Like the others, the epitaph on the Cathedral front does not tell her “story”. It only gives us the city’s official version as seen by Pisans at the time.

In his own tongue Timino swore to God that from then on he would respect his agreement not to harass Christians nort to exact taxes from Pisans and Genoese and to treat them forever as his masters.